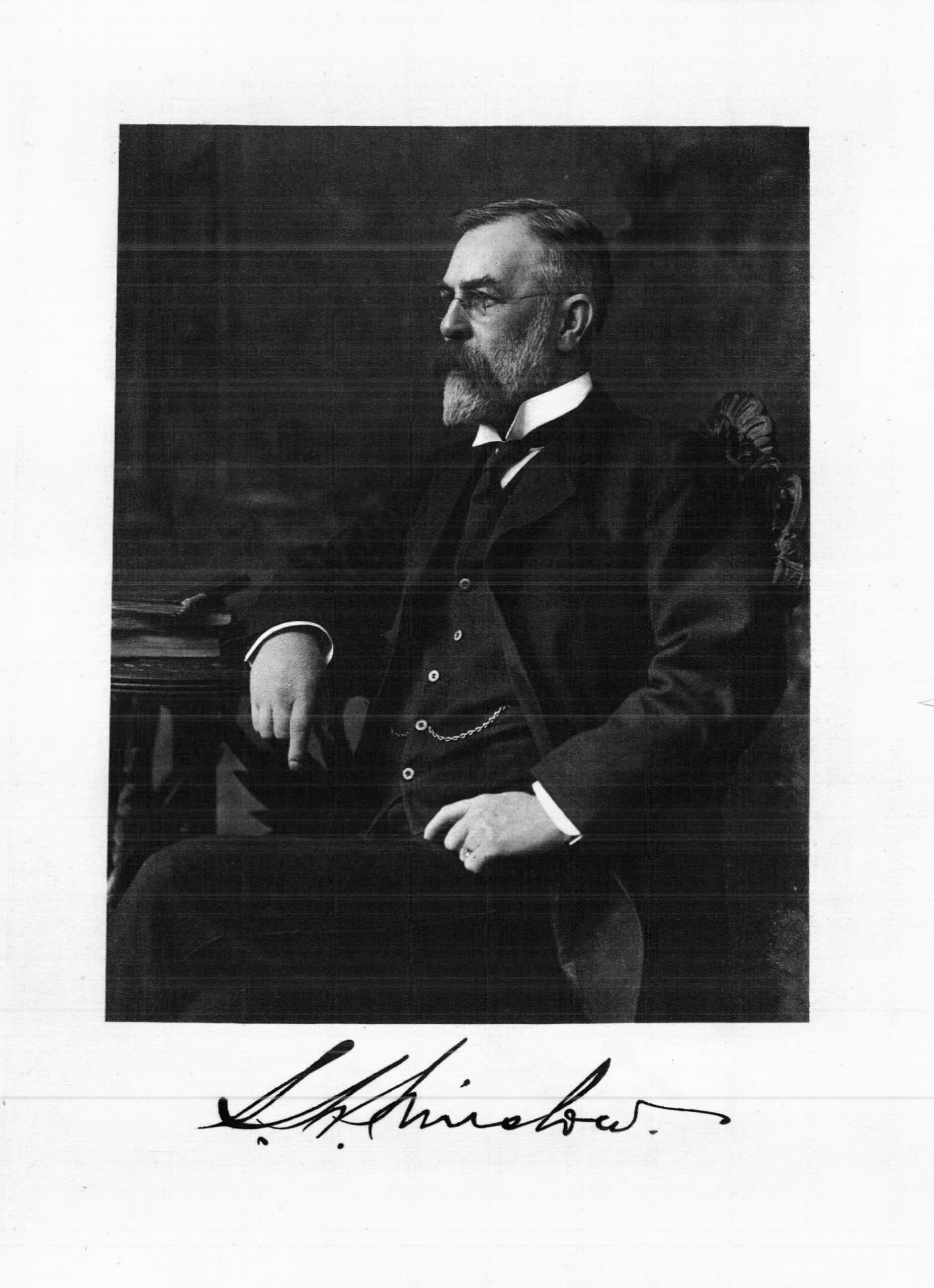

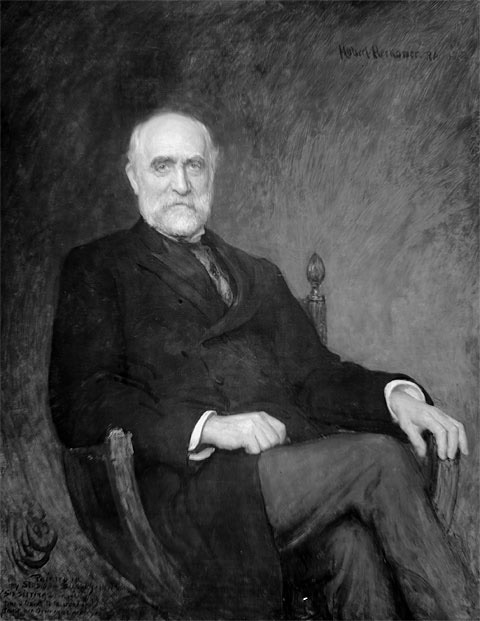

Sidney W. Winslow, president of the United Shoe Machinery Company, died on the evening of Monday, June 18, 1917, at his former home on Cabot Street, in Beverly, Massachusetts, in his 63rd year. His death, the announcement of which came with a shock of sad surprise, was due to heart failure, following a slight attack of ptomaine poisoning, which had kept him to his rooms in Boston only a few days. On Saturday he was taken to the house in Beverly, now occupied by his son, Sidney W. Winslow, Jr. and there the end came peacefully.

For nearly a year, Mr. Winslow had suffered from nervous exhaustion, due partly to an attack of grip, but more to his ceaseless attention to the cares and responsibilities of business, and last Winter he passed much of the time in the South in an unsuccessful endeavor to regain his health.

Sidney Wilmot Winslow, organizer and president of the United Shoe Machinery Company since its formation in 1899, occupied the position of one of the great leaders in the industrial world the natural course of things. His father was a shoe manufacturer and inventor of shoe machinery, and the boy when in his teens was familiar with the tools of St. Crispin. Then for fourteen years he worked in his father’s factory, becoming familiar with every one of the early shoe-making machines. As a young man he recognized, as did his father, the tremendous future possibilities of machinery in the shoe manufacturing industry, and before he was thirty years old had a controlling interest in the manufacture of one of the earliest machines used in shoe-making. Thus from inheritance and the associations of his youth Sidney W. Winslow possessed the foundation a commanding success. He saw the future, grasped the present, mastered his subject, and in 1899 with rare business ability organized the company which by efficiency and services done so much for the shoe manufacturing industry and the wearers of shoes.

Ancestry and Early Activities

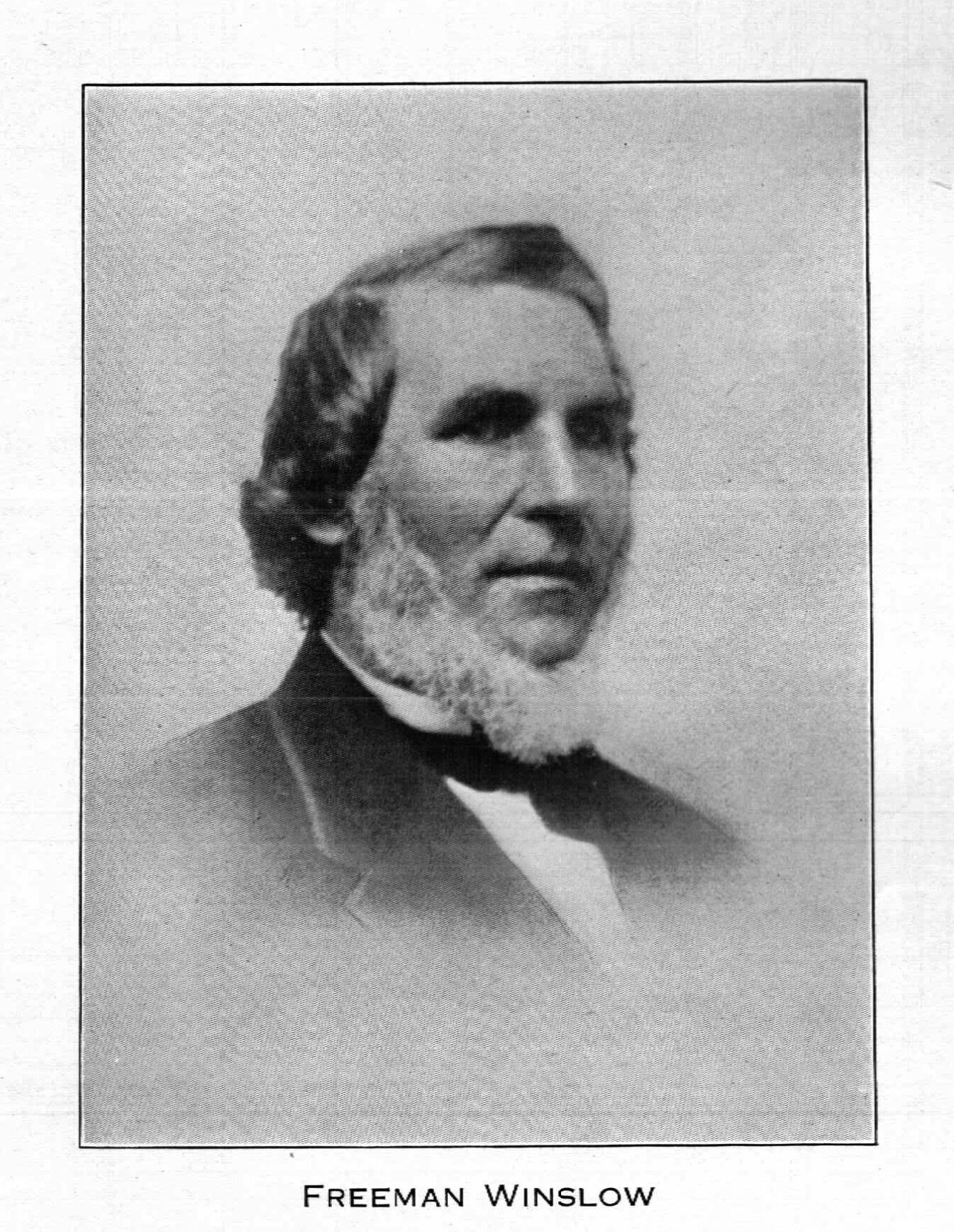

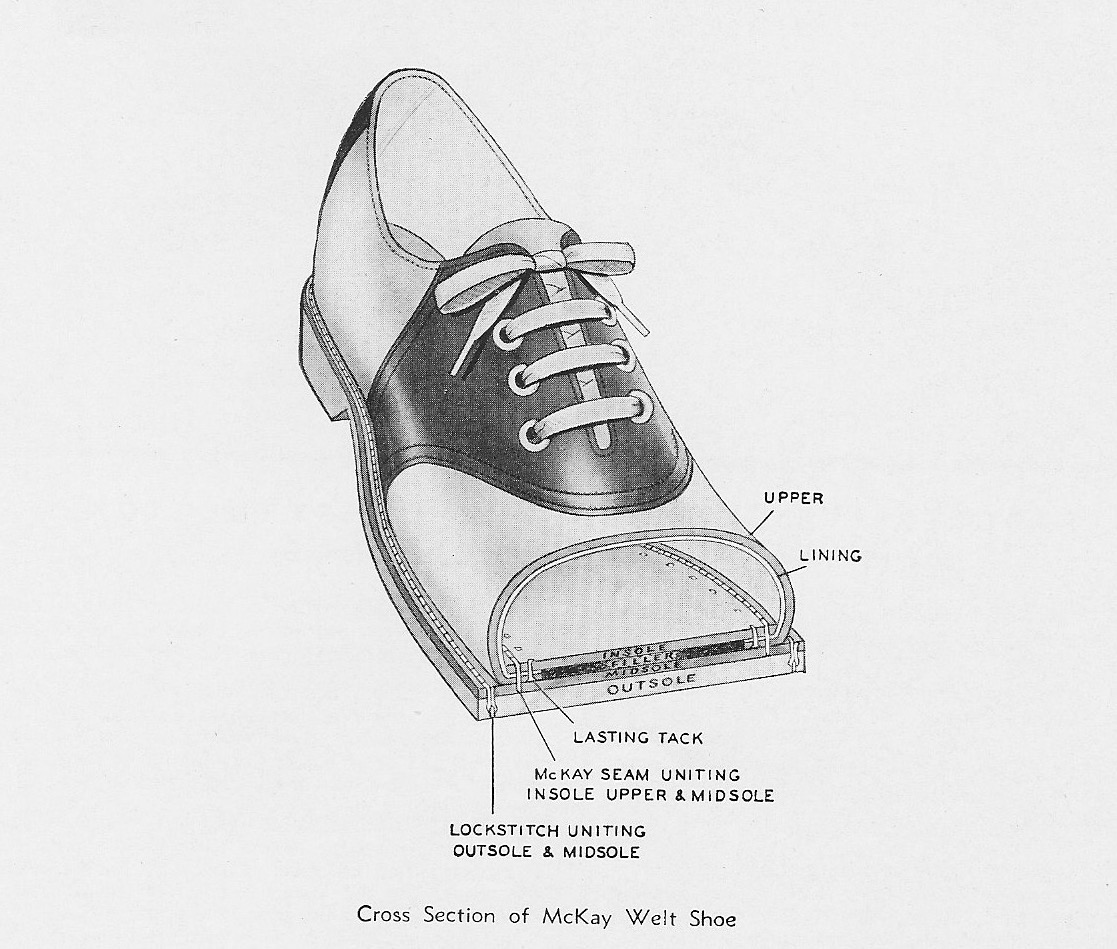

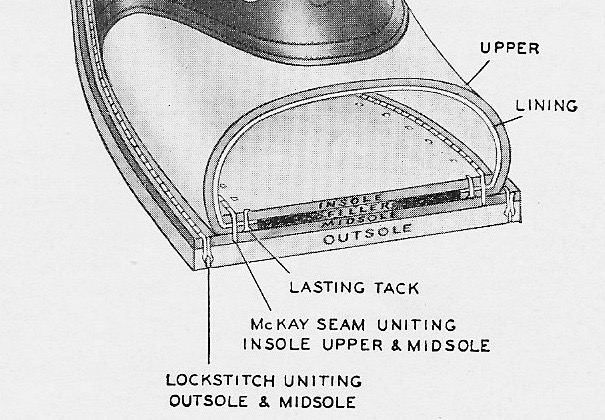

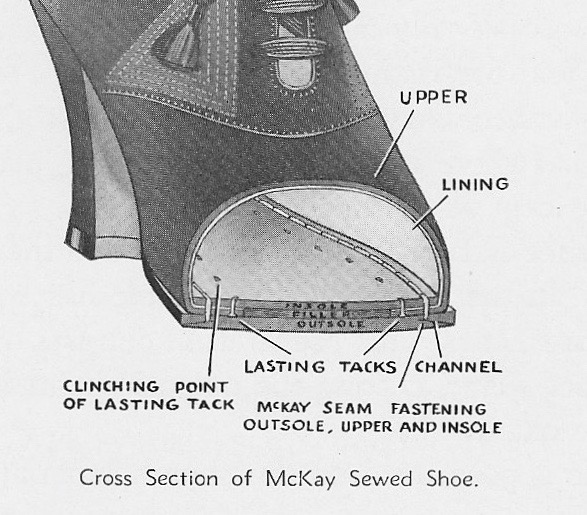

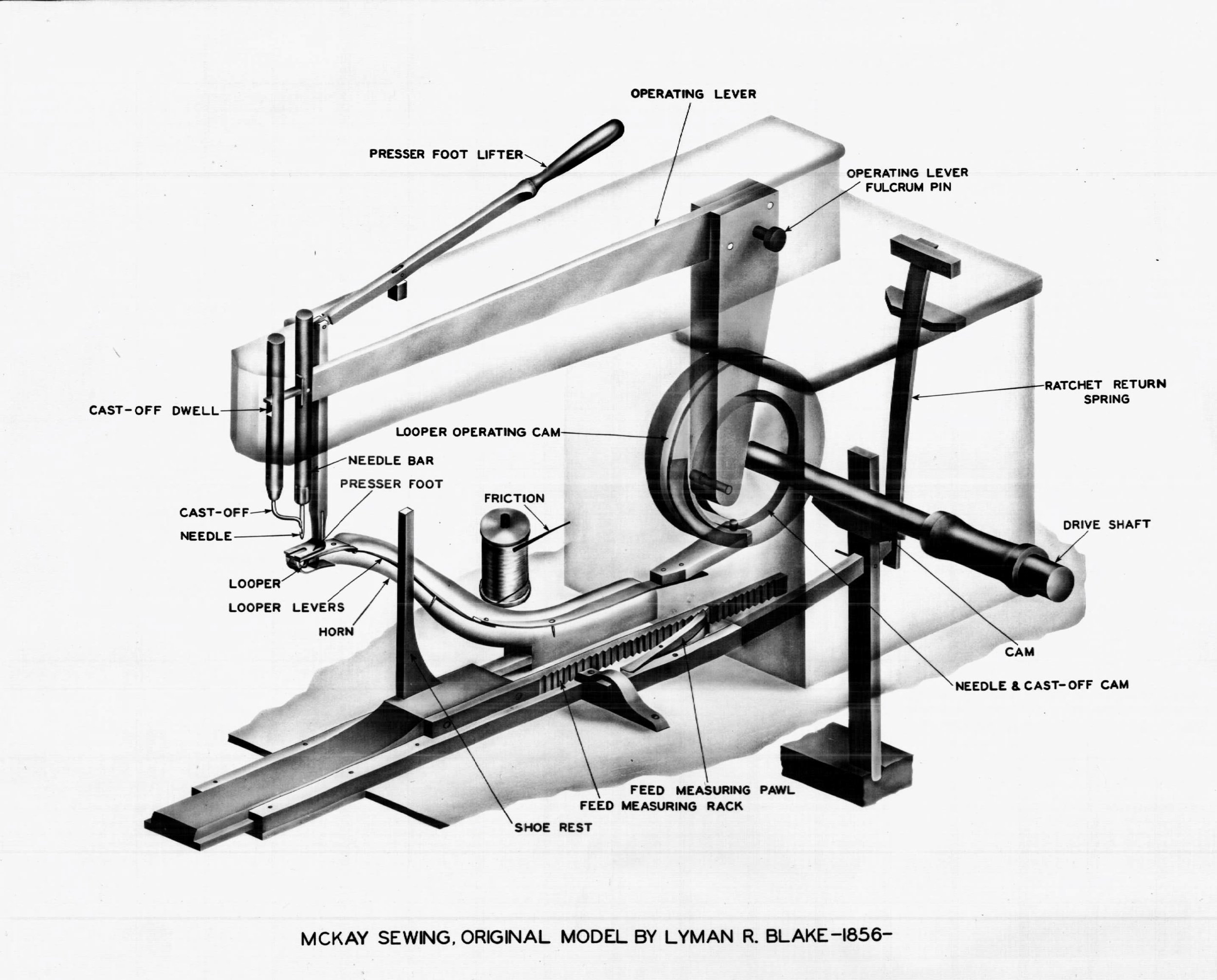

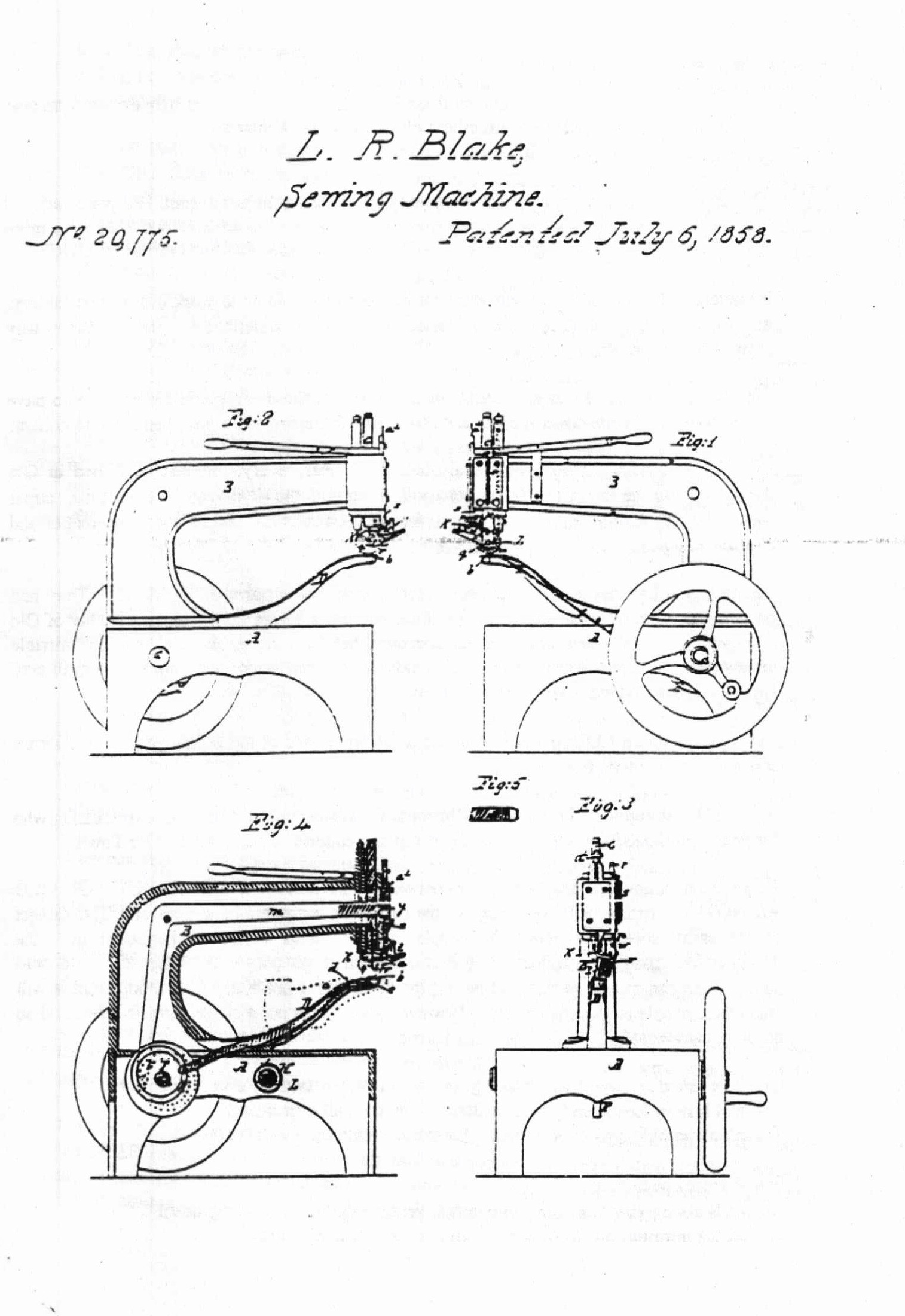

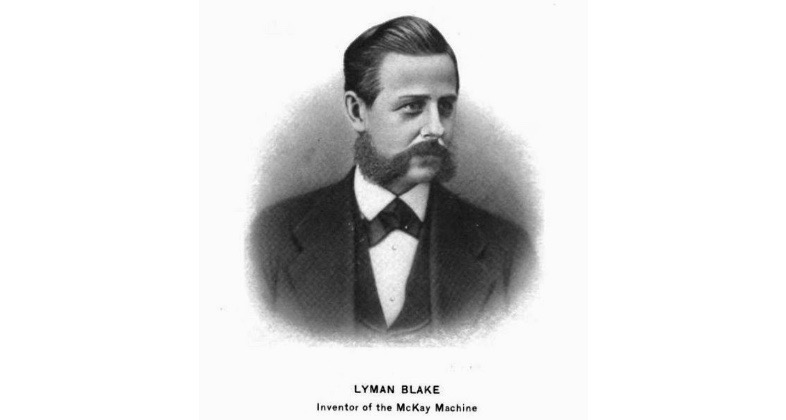

The son of Freeman and Lucy H. (Rogers) Winslow, Sidney Wilmot Winslow was born in Brewster, Massachusetts, on September 20, 1854, being a descendant on his mother’s side from Thomas Rogers, a passenger on the Mayflower, and on his father’s side from Kenelm Winslow, an early settler on Cape Cod. During his boyhood his father moved to Salem, Massachusetts, where he attended the grammar and high schools, later going to work in his father’s shoe shop. This was half a century ago, when shoe machinery was in its infancy. The McKay sewing machine, which sewed the soles of shoes to the uppers - a machine which marked the beginning of the supplanting of hand labor by machinery - had only recently been introduced into shoe factories. From time to time other machines were developed and young Winslow, who rose to be foreman of the stitching room in his father’s factory, became thoroughly impressed with the growing importance of shoe machinery.

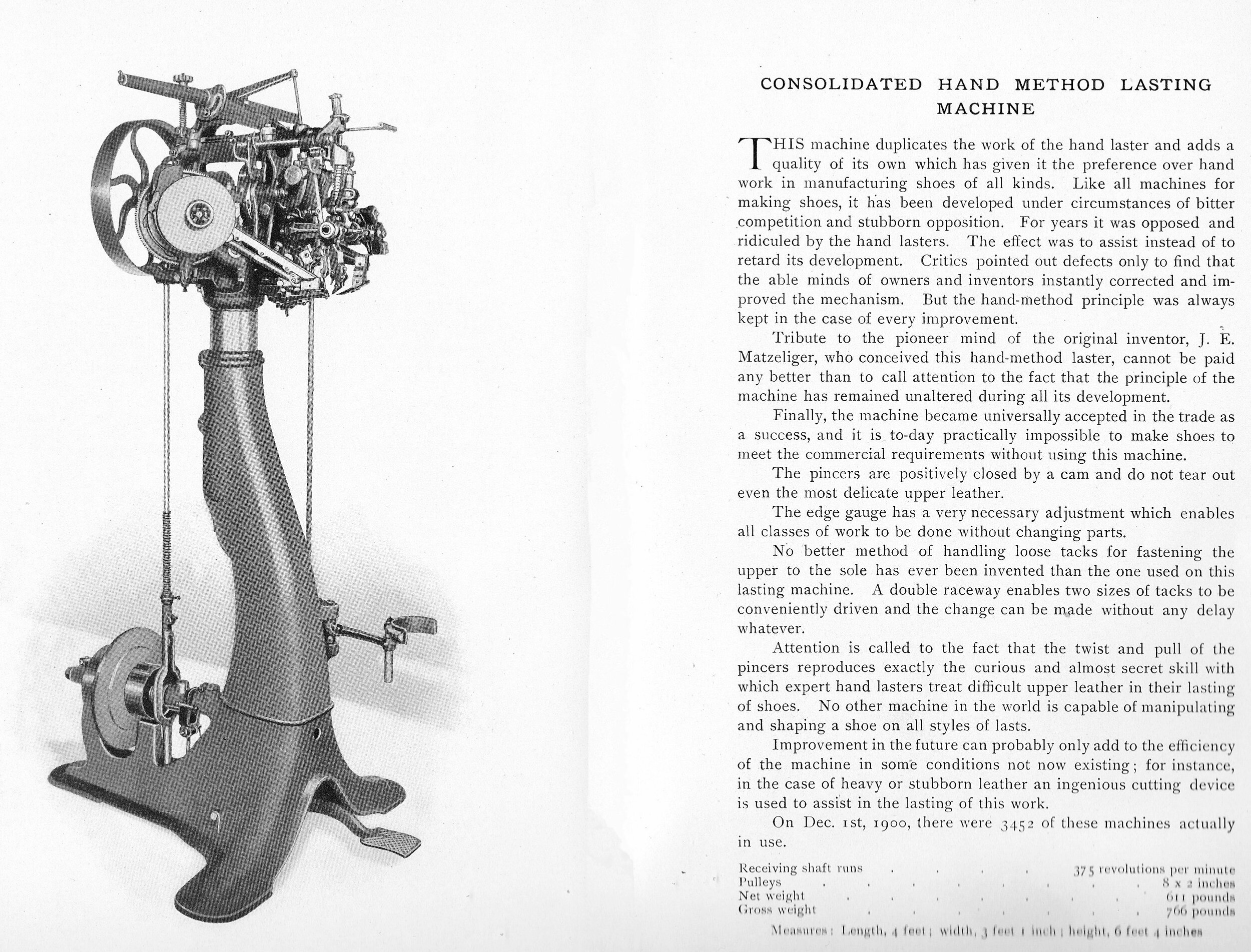

In 1883 he secured a controlling interest in the Naumkeag buffing machine, invented by his father. Later, he took hold of the hand lasting machine, the invention of Jan Ernest Matzeliger, a native Dutch Guiana living in Lynn. The idea that machinery could ever do the work of hand lasters had always been ridiculed, but Matzeliger solved the problem and the principle of his machine has remained during all its subsequent development. Mr. Winslow saw the value and the possibilities of of this invention at the start, and in the 1890s made a commercial and financial success of it.

The Matseliger Patent

The USMC Catalog page.- The Matseliger Machine - One of several versions.

Organization of the United Shoe Machinery Company

Inventive genius applied itself vigorously to shoe machinery during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, until its close there were many machines adapted to the various operations in making shoes and often several adapted the same operation. A new company had sprung into existence with each new machine, and many of them had a struggle to live. This multiplicity of separate companies made it difficult for shoe manufacturers. By degrees, however, the smaller concerns went out of business and in 1899 the manufacture of shoe machinery was largely concentrated in three companies, the Consolidated & McKay Lasting Machinery Company, the Goodyear Shoe Machinery Company, and the McKay Shoe Machinery Company, each of which respectively made and leased machines adapted to a particular class of operations, and not competing with one another.

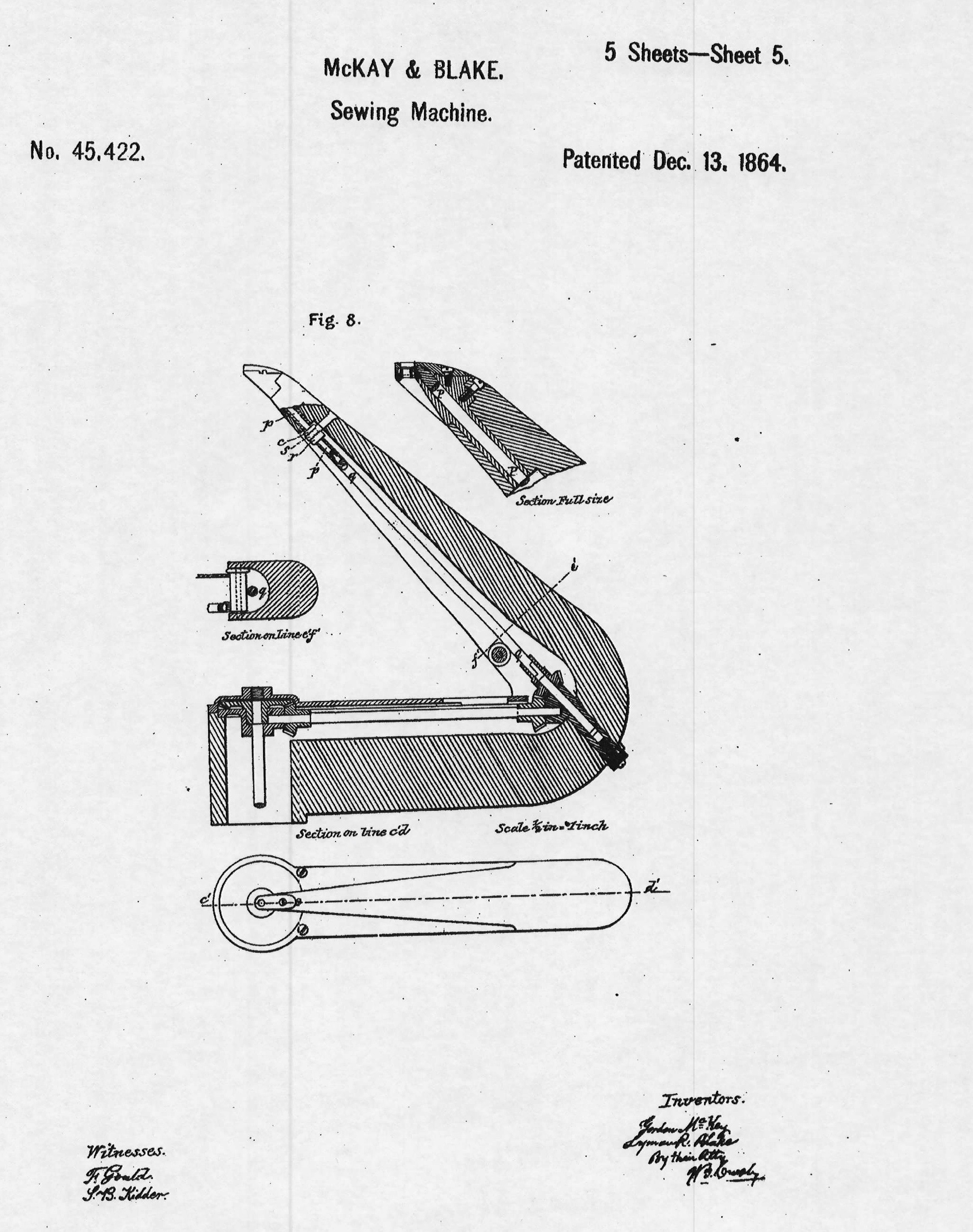

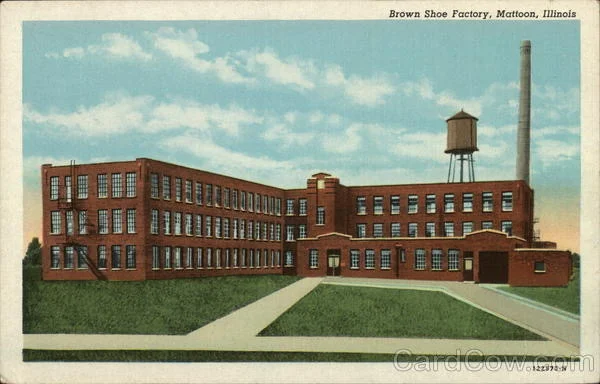

Factory of the Goodyear Shoe Machinery Company

The Goodyear Stitcher

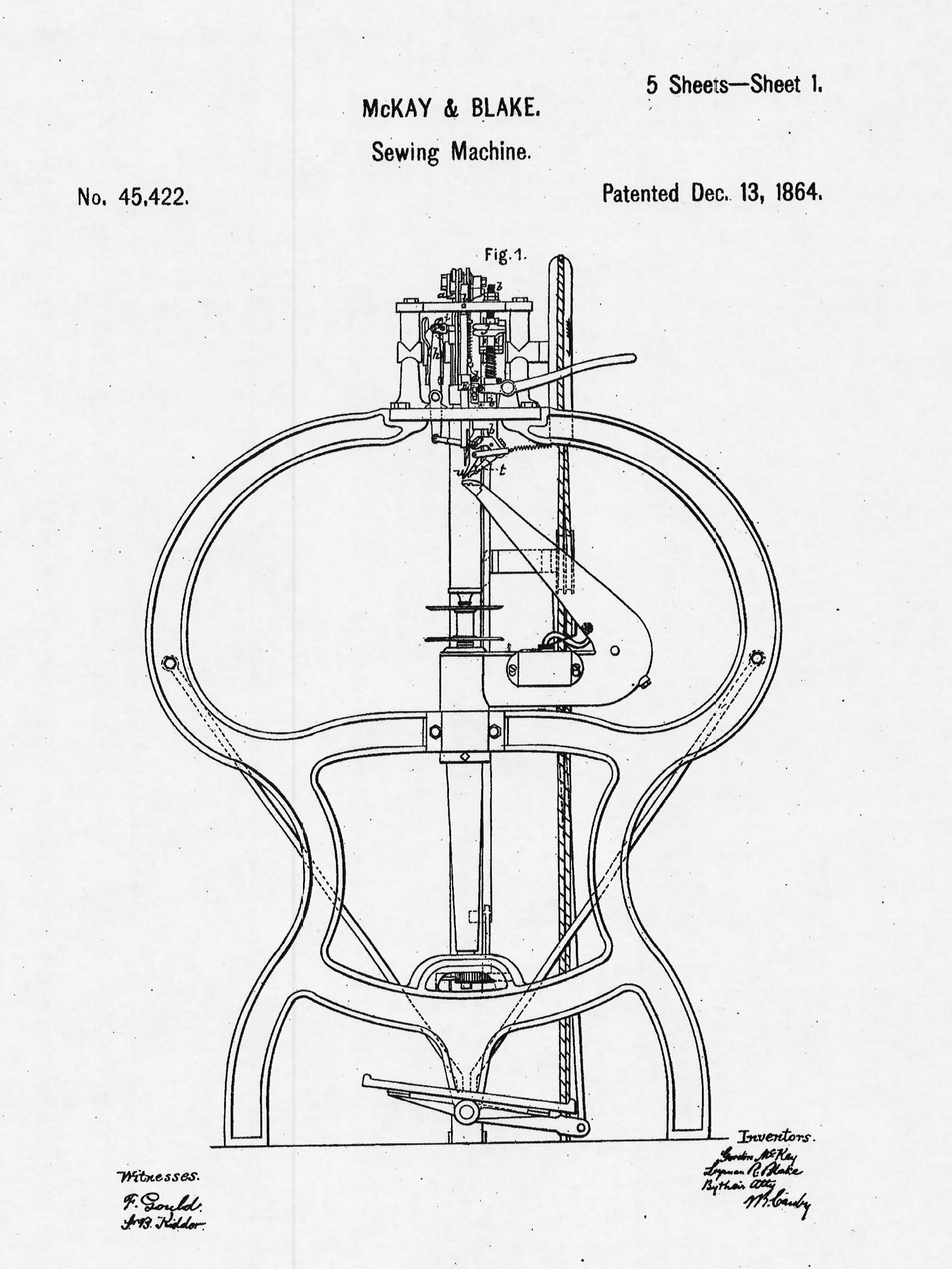

The McKay-Blake Sole Stitching Machine

Still impressed with the importance shoe machinery as an industrial factor and more and more with the economic waste both labor, capital and the public caused by a multiplicity of companies making shoe machines, Mr. Winslow took the initiative in improving the situation, and the three companies just mentioned were consolidated in 1899 under the name of the United Shoe Machinery Company. Mr. Winslow was chosen president the company, a position which he filled until his death.

Mr. Winslow was also president of the United Shoe Machinery Corporation, of the United Shoe Machinery of Maine, president and director the Beverly Gas and Electric Company, treasurer and director of the Naumkeag Buffing Machine Company, director of the Newburyport Gas and Electric Company, the First National Bank of Boston, the United Smelting, Refining and Mining Company, and Island Creek Coal Company and a director in many other companies.

That Mr. Winslow should become a business and financial leader was inevitable. His life-long knowledge of shoemaking and shoe machinery, his constructive vision, his genius for organization, his great capacity for work, could lead to no other result. Success and supremacy come to such men because it is earned and because their qualities are those which must make for leadership of men and of industry.

The Result of Constructive Leadership

Prior to 1850 practically every shoemaking process was a hand process. With the advent of shoe machinery the methods of centuries rapidly changed. Today a machine performs each of the early process with greater accuracy rapidity, and economy. In no other industry has the introduction of machinery been more complete or more revolutionary. During the last twenty years the growth of the boot and shoe industry has been phenomenal, due to standardization co-operation, the greatest change from former conditions being regard to shoe machinery.

Today (1917) manufacturers, large or small, can obtain machinery on equitable terms, with special privilege to none. Machinery is the only item in the cost of a shoe which is not higher than when the United Shoe Machinery Company was formed in 1899. Through its wonderful products and far-reaching expert service, the United Shoe Machinery Company lowers the cost of manufacture, simplifies the problems and facilitates the business every shoe manufacturer and retailer, and helps to bring the best shoes within the reach of the people - with the public the ultimate gainer.

The Winslow Mausoleum in Beverly, Massachusetts.

Social and Personal

Mr. Winslow was a member of the Commercial, Algonquin, and Boston Chess clubs. His recreations were chess, tennis, and golf - and he played as he worked, with all the energy and force he possessed. And it was characteristic of him that he believed there is still room at the top for young men who are diligent, wide-awake, and alert to seize opportunities.

In 1877 Mr. Winslow married Georgiana, daughter of George Buxton of Peabody, Massachusetts, and had four children; Sidney W. Winslow, Jr., Mrs. Lucy Hill, Mrs. Mabel W. Foster, and Edward H. Winslow. He was a resident of Orleans, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod, and lived during the Winter at 10 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston.

Above text is from a Remembrance published in the USMC Newsletter, The Three Partners, shortly after M. Winslow’s passing. Images are from the Editor